Skeletons as a Service. Part 1: Startups

Somewhere, something, went terribly wrong!

A software startup is, in its essence, a hypothesis. A tentative combination of technology, market timing, and belief in a user need that might not yet exist. It carries the posture of innovation, but beneath that, it is a fragile construct. A prototype of a business model wrapped around assumptions waiting to be tested. The product is a manifestation of these assumptions, an interface layered over uncertainties about usage, adoption, pricing, and retention. Before it is a company, it is a question.

But this question is posed to a market that is not static. It is dynamic, multi-dimensional, and entangled with variables far beyond the startup’s scope or control. Economic conditions shift. Legal frameworks evolve. Competitors pivot or collapse. Technical landscapes change rapidly. Even the internal rhythms of decision-making can create fault lines. Each of these vector, business, software, legal, economic, can become a source of pressure. In time, some of these pressures manifest as crises. Whether or not they become fatal depends on the antifragility of the startup, or to put it in another way, how many “skeletons has in its closet”.

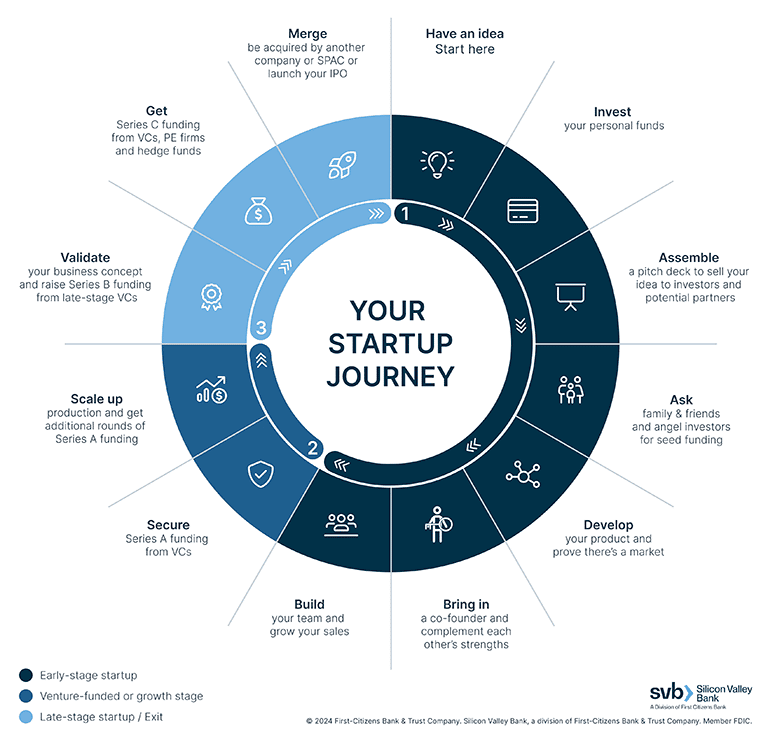

The lifecycle of a startup

This graph originates from Silicon Valley Bank’s article titled “What are the three stages of a startup?” [1]. I referenced these stages during my talk at the InnerSource Summit 2024 [2] international conference to describe the evolution of InstaShop, the company I currently serve, as it progressed from startup to acquisition by a publicly traded company. InstaShop successfully gone full-circle, passing through each of the three stages described. Not all startups, however, have this luxury. In fact, 90% or more of them, fail!

The early stage of a startup does not begin with scale but with a question. There is a kernel of an idea, sometimes born out of persistent frustration, other times from a moment of clarity, suggesting that a product or service could be viable under the right conditions. This phase involves defining the problem and shaping the first response. The team is small, risk is high, and most commitments are personal rather than formal. Resources tend to be limited and improvised. It is in this environment that the initial product takes form, often alongside the first attempts to raise funding. Support commonly comes from friends, family, or personal savings. Accelerators may enter the picture once the team has built something more tangible than an idea.

The venture-funded stage begins with the arrival of Series A capital. At this point, the focus shifts from potential to performance. Investors come with expectations, and the business must demonstrate its ability to grow. The company is now expected to scale its operations with a clear plan, a structured team, and a functioning sales strategy. Founders take on new responsibilities, often moving away from execution and toward leadership. As the company grows, it must remain responsive to changing conditions and willing to adapt. Each funding round depends on the outcomes achieved during this stage. This is where theoretical value must be proven through practical results.

In the late stage, the startup increasingly takes on the structure and responsibilities of a mature company. Financing stabilises, and revenue is no longer speculative. Strategic expansion becomes a central focus. The company may consider entering new markets, expanding its product offerings, or exploring acquisitions. Fundraising remains important but is now driven by demonstrated performance. Founders often face the decision of whether to continue leading or begin planning an exit. At this point, the market that once challenged their idea may now be prepared to acquire it. Yet, even in this advanced phase, the core question persists: how to build a business that does not just endure pressure, but improves because of it.

Common business startup mistakes [3,4]

1. Selling to the Wrong Customers: It is tempting in the early days to take any deal that comes your way. But not every customer is a good fit, and those who are only loosely aligned with your core offering will eventually churn, drain your support resources, or damage your reputation. Building a disciplined qualification process early is not a luxury, but a necessity for sustainable growth.

2. Underpricing and Poor Monetisation Strategy: Setting your price too low, either out of fear or in a misguided attempt to gain market share, signals a lack of confidence and risks anchoring your product as low value. At the same time, overcomplicating pricing or failing to tie it to customer outcomes can block adoption and reduce your perceived impact. Pricing must be tested, validated, and continuously aligned with how value is delivered and experienced.

3. Overbuilding Before Core Value is Proven: Many startups add features too quickly, trying to be all things to all users before they’ve demonstrated their core utility. This leads to bloated products, longer onboarding, and higher support costs. Start with the smallest, clearest version of value, then evolve based on actual customer behaviour and needs.

4. Failing to Build Around Retention and Expansion: Focusing exclusively on acquisition is a short-sighted strategy. Your existing customers are a richer source of revenue and insight than cold prospects, especially in subscription models where retention, upsell, and advocacy drive growth. Build your sales, success, and product functions with customer lifetime value in mind from the outset.

5. Misusing or Neglecting Sales Technology: Technology should serve your sales strategy, not complicate it. When properly selected, integrated, and used, sales tools enable faster feedback loops, better visibility into the funnel, and more time for meaningful conversations. But without the right setup, training, and process discipline, they become expensive distractions.

6. Hiring Sales Reps Too Early Without a Proven System: A common pitfall is bringing in sales hires before there is a repeatable and documented process for finding, qualifying, and converting leads. Even experienced sales professionals will underperform if thrown into an undefined system. Before hiring, ensure you’ve built the basics: a validated ICP, a tested pitch, and a reliable lead generation mechanism.

7. Trying to Do Everything Alone: Founders often carry the full weight of vision, product, and sales. But as the complexity of growth increases, so does the need for external input. Seeking out mentors, advisors, or strategic partners is not a sign of weakness; it is an operational strength that accelerates clarity and builds robustness into your go-to-market approach.

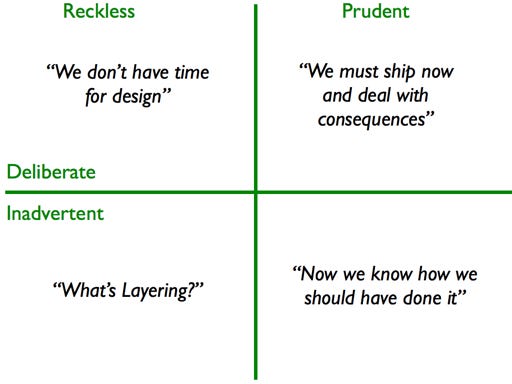

THE mistake! Also known as Technical Debt

Technical debt [5] is a powerful metaphor for deficiencies in internal software quality that slow future change. As Martin Fowler explains, it surfaces when our system accumulates “cruft”—architectural, design or coder‑level issues that make adding new features harder than it should be. For example, a muddled module structure might take a developer six days to extend rather than four; the extra two days are interest on the debt. The metaphor helps us frame trade‑offs: deliver quickly now, or invest time in internal quality so that the future becomes easier.

But as Uncle Bob argues [6], not all bad code qualifies as technical debt. He draws a distinction between deliberate, managed compromises and reckless messes. A team may choose a sub‑optimal design for legitimate business reasons, fully aware of the cost and committed to pay it off later, this is true technical debt. In contrast, when poor design arises through laziness, ignorance or lack of discipline and there is no plan for remediation, it is simply a mess, not a debt. The mess will eventually choke the architecture and erode team productivity regardless of whether it was intentional.

Managing technical debt therefore becomes a matter of strategy and discipline. It is unwise to pretend that every shortcut is safe; we must treat debt like a financial obligation, some of it we may choose intentionally, but we must track the balance, pay the interest and gradually reduce the principal. Fowler recommends incremental “pay‑down” of cruft by refactoring areas we modify often, since the interest payments there are highest. Uncle Bob emphasises that taking on debt still requires cleanliness: the code created under the compromise must be maintainable, testable and refactorable, otherwise you’ve simply created a mess.

Ultimately, the question is not whether your system has flaws (every evolving software system does) but whether you treat them as manageable debt or uncontrolled mess. Internal quality is not a luxury; it is the fuel that enables speed, adaptability and antifragility. By being deliberate about the debt we accept, transparent about the cost, and disciplined about the payment, we build systems that do not merely survive change, but thrive because of it.

Final thoughts

A startup must not confuse early traction with stability. What it builds, how it sells, and who it serves are all subject to volatility. Pitfalls are not always dramatic collapses. Often, they are silent inefficiencies, decisions made under pressure, or compromises never revisited. The startup that survives is not the one that avoids all mistakes, but the one that learns how to surface them early, understand their impact, and build stronger processes in response. Whether the problem lies in misaligned customers, rushed pricing, overbuilding, or neglected code quality, each mistake leaves a trace. Startups should monitor these traces carefully, not to avoid failure, but to metabolise it into capability.

This is where the concept of antifragility becomes essential. It is not enough to remain operational in the face of stress; a company must grow more resilient because of it. Antifragility comes from feedback loops, from actively confronting what went wrong and iterating forward with intention. This includes managing technical debt deliberately, building quality into high-velocity areas of the codebase, and recognising when speed has quietly turned into drag. It also means knowing when to slow down, when to refactor, when to listen. Startups that treat every feature shipped, every deal lost, every spike in support tickets as signals rather than setbacks are the ones that stand a chance to grow past the fragile beginnings and into something more durable.

References

Silicon Valley Bank. What Are the Three Stages of a Startup? SVB.com. Published April 2022. Accessed November 5, 2025. https://www.svb.com/startup-insights/startup-growth/what-are-the-three-stages-of-a-startup/

Kritikos A. When There Is No Alternative to InnerSource. YouTube. Published December 5, 2024. Accessed November 5, 2025. Kritikos A. When There Is No Alternative to InnerSource. YouTube. www.youtube.com/watch?v=yvTn5DGvSA0

de Vonarkha‑Varnak J. Six Common Sales Mistakes SaaS Startups Should Avoid. Salescode.io. Published April 25, 2022. Accessed November 5, 2025. https://salescode.io/en/blog/six-common-sales-mistakes-saas-startups-should-avoid

Common Mistakes in SaaS Business and the Best Ways to Avoid Them. Medium. Published February 2022. Accessed November 5, 2025. https://medium.com/startup-insider-edge/common-mistakes-in-saas-business-and-the-best-ways-to-avoid-them-2f18cbb3c6bb

Fowler M. Technical Debt. MartinFowler.com. Published May 21, 2019. Accessed November 5, 2025. https://martinfowler.com/bliki/TechnicalDebt.html

Martin RC. A Mess Is Not a Technical Debt. Uncle Bob Consulting LLC. Accessed November 5, 2025. https://sites.google.com/site/unclebobconsultingllc/a-mess-is-not-a-technical-debt

Fowler M. Technical Debt Quadrant. MartinFowler.com. Published October 14, 2009. Accessed November 5, 2025. https://martinfowler.com/bliki/TechnicalDebtQuadrant.html